The Evolution of Camera UIs Part 2 — Canon’s Modern Film and Early Digital SLRs

In the first part of this series, I looked at some of the theoretical aspects of UI design and some of the bigger picture concepts.

This time, I’m going to look at the evolution of Canon’s film SLR UI as it developed into their earliest DSLRs and how those designs became the stepping stones for today’s cameras.

However, as I’ll probably repeat over and over, DSLRs didn’t happen in a vacuum. Maybe more importantly, technological advances in the 1980s opened up and set the stage for doing may of the things that modern camera UIs do, and Canon was quick to start exploiting that. However, effectively exploiting new technologies is never something that happens overnight.

Film

Okay, film is not a user interface — clearly.

However, cameras don’t exist in a vacuum, and to talk about the evolution of DSLR user interfaces, you have to talk about the evolution of film cameras, and consequently the limitations, mechanics, and behaviors imposed by film.

DSLRs weren’t developed in vacuum, they were developed by existing camera makers, and those companies had existing film cameras with existing interfaces. In this early years, DSLRs often directly used film SLR bodies as the basis for their own chassis.

More importantly, at least for this story, is that the mechanics of the medium directly impact the interfaces that were designed for the cameras. The transitional period from film to digital was, to a very large degree, a process of figuring out how the changes in technology would change the way the cameras were used.

While most people think about film in terms of the medium, its limitations and mechanics have a deep impact in how SLR interfaces evolved and how photographers worked. Many things we take for granted today with digital cameras, while technically possible to do with film, were impractical at best. Bear in mind, I’m not talking about things like being able to review and image here either, the things I’m talking about much more fundamental.

For example, in the digital world it’s an entirely reasonable process to change cards before one is full. Say you might have a slower but larger card in your camera and want to use a faster card for shooting some video or something like that. While you could change film out before completing the entire roll, it wasn’t something you wanted to do regularly. Moreover, you often would write off whatever frames you didn’t shoot due to the difficulty of reloading the half used roll and not messing up some frames.

That said, all film SLRs had a mechanism to manually rewind the film before the roll was completed. However, you wouldn’t use this casually.

For that matter, photographers generally wouldn’t carry loads of different film speeds either. At least this was never my experience either shooting film or from people I know. You might have a daylight balanced ASA 100 film for daytime use and a faster tungsten film, say ASA 400 or ASA 800 for night time use or something like that, but you’d generally stick to one speed for an extended period of shooting.

Even considering push and pull processing, film speeds couldn’t practically be changed on a per frame basis.

Between the way photographers worked, that is mostly shooting one film speed at a time, and the limitations of developing the film, the simple reality is that you couldn’t change film speeds on a per frame basis. The camera UI’s only exposed the ASA setting as much as was necessary to allow it to be input.

In fact, one of the late film technologies was the introduction of DX coding on the film canisters. This used conductive patches to identify the film speed, number of exposures, and exposure tolerance to the camera. DX coding further pushed the idea of setting an ISO as a useful control even further away from the forefront of photographer’s minds — their choice of film set the film speed.

Between the practical and behavioral aspects of shooting with film, and the of DX coding, film speed was not an practical exposure handle. Consequently, in designing the camera’s interface, there was little need to make the ISO setting easily alterable[1].

Note, the A-1 like the AE-1 was an electronic camera, however, it’s control layout retained the same design as the purely mechanical cameras that preceded it.

My focus on ISO/ASA here isn’t an accident. Of all the major differences between film and digital, this is the one aspect that is easily the most defining and most notable in the the development of DSLR UIs. In fact, I consider it one of the major milestones in a manufacturer’s UI design when they understand the value of making it easy to change the ISO on their cameras and make it a highly accessible function.

The broader impact of film on DLSR development, however, is in the way it’s limitations and characteristics fed back into the behaviors of photographers, and in turn back into the camera designs through the photographers on their advisory panels.

Humans, Adaption, Feedback, and the Evolution of UIs

This brings me to a human element in interface design: users have a very hard time predicting what they will want when there’s a fundamental technological shift.

Steve Jobs was famous for saying that users don’t know what they want. To a limited extent there is a grain of truth to that, but perhaps not in the way that most might think.

To start with, people adapt to the situation that they’re in and eventually it just becomes normal. Film imposed a certain set of behaviors around how a camera was used. Moreover, it was doing this for more than 60 years by the time that digital cameras were starting to appear. That’s a long time to establish behaviors around the limitations imposed by a technology as normal.

Secondly, not a lot of people have the right kind of creativity to see and recognize the way that fundamental shifts in technology will have fundamental shifts in the way things can be used. Part of this goes back to the established behaviors thing, but part of this is simply recognizing the impacts of something completely new and different.

Finally, many, if not most, pro photographers are extremely conservative and strongly ingrained in their ways. In many ways it’s the nature of being reliant on something for your living. Their cameras are the lifeblood of their livelihoods, that alone will make you more conservative about changing something that works.

When you combine these factors, change doesn’t happen overnight. Someone in the right place, either an engineer or a prominent enough photographer that camera makers will listen to them, has to recognize the importance of a new control and speak up. Further, it has to deliver enough of a benefit that those that didn’t recognize the benefits themselves, will see enough of a benefit in practice that they don’t oppose the changes so heavily as to kill them.

There’s a couple great example of how the status quo and the difficulty of imagining improvements have influencing designs. When Canon released the EOS 5D mark II, they were criticized by many for not improving the AF system[2], especially when the Nikon D700 had the same AF system as their pro-level D3. Canon’s response, paraphrased, was that they asked their 5D users (read advisory panel/established pro photographers) and they said that the AF system was fine for their uses.

Another, perhaps better, example of this kind of thing, and one that I’ve seen first hand is the accessibility of the ISO button. Canon realized that the ISO was something you would change frequently on a digital camera, and back in 2005 started making the ISO control more accessible. On the other hand, Nikon kept the ISO button almost as far away from anywhere you’d be able to get to while shooting as possible.

The vast majority of the serious, and especially long time, Nikon users I had talked in the early 2000s to never saw any benefit to moving the ISO button closer to the shutter release. There was always a level deference to the status quo, “Nikon doesn’t do it that way, so there’s no point in complaining about it.”

That was, at least, until Nikon actually made it possible to move it to a button near the shutter release. When the D4 and the D810, the offered the ability to remap the movie recording button near the shutter release to control the ISO. All of a sudden every Nikon pro was crowing about how you need to do this because it made shooting so much better.

I can almost guarantee that a big part of that change not happening sooner was that when Nikon was soliciting feedback from their ambassadors and other high end users, and this wasn’t something they were even talking about. If they had been, I’m confident that Nikon would have made the change a lot faster than they did[3].

Foundations of Canon’s Modern SLR UI

In a way surprisingly similar to the early 2000s, the late 1970s and 1980s were a period of substantial technological change in camera design. Complex electronics, things even as complicated as micro-processors, were becoming economically viable to integrate into cameras with increasing reliability and complexity.

By the mid- and late 1970s cameras were increasingly becoming dependent on electronic control in lieu of purely mechanical operation. However, in a process similar to the transition from film to digital, the camera designers and users took some time to make the transition.

Canon’s released their first SLR that was dependent on electronics for basic operation in 1976 with the AE-1. However, it would take until the T50 in 1983 before technology and Canon’s designers would begin to change the UI to reflect the flexibility that electronic interfaces allowed.

A mere 2 years after the release of the T50, Canon would release an SLR with an interface that would lay the foundations for their cameras to this day. This camera was the T90.

Fundamentally, Canon’s DLSR, mirrorless, and even compact camera UIs are built on a design that was laid down more then 30 years ago. While the details change, the longevity of the overall design is a testament to just how well the T90s designers did in getting the UI design right.

With the availability of compact incremental rotary encoders, and more importantly economical compute power and memory to be able to track settings, Canon’s designers could start to design hardware that exploited the power of electronics to simplify and improve user interfaces instead. This marked a change in camera UI design where a focus could be placed on the user first, instead of balancing the usability with the limitations of the underlying mechanisms.

This problem seems trivial by today’s standards. An incremental rotary encoder can be had for less than $2 in small quantities, and a micro-controller capable of doing something useful with its output can be had for even less.

However, if you dig through service manuals for electronic cameras in the late 70s, you won’t find this kind of technology being used at all. Instead, early electronic cameras used absolute rotary encoders, instead of the incremental ones that are far more common today. These encode the absolute position of the dial, not the relative state that it’s being rotated and by how much.

Absolute encoders have some advantages though, especially in a time when computer and memory technology is severely constrained. With an absolute rotary encoder, the encoder itself provides the memory needed to store it’s setting. It’s outputs can be directly connected the camera’s logic for whatever it’s controlling. Since every position is an absolute, the position for, e.g. ASA 200, will always be the position for ASA 200 and this can be relied on.

Moreover, since the encoder itself is its own memory, the logic for processing it can be much simpler. The “processor” doesn’t need to detect that changes are happening and increment or decrement a variable in another memory location to reflect those changes.

On the other hand, an incremental rotary encoder, just tells a processor that it’s being turned and in which direction. There has to be some form of processor with storage to understand, first, what that encoder is actually controlling, and, second, what the setting was, how it should be changed, and to change it.

While an absolute rotary encoder does make it easier to do electronic controls with very limited computational power, it also means that controls must mimic their mechanical camera counter parts much more closely. That is, the camera needs separate dials for things like shutter speed and ISO, and those dials need individual positions for the settings they’re supposed to support.

With the shift to incremental rotary encoders, it becomes possible to use one encoder to control many functions. Moreover, its function doesn’t need to be fixed, instead it can be changed to be whatever is most valuable in the current situation. So a single dial can be used to set the shutter speed in shutter priority, the aperture in aperture priority, the program shift in program AE, exposure compensation, ISO, change AF points, and so forth.

In doing this, Canon’s designers opened up a number of doors. To start with, smaller incremental encoders allowed them to position the dial so it rotated vertically behind the shutter release on the top of the grip.

Having the dial in this orientation makes it easier to rotate with a finger while maintaining your shooting grip on the camera, as opposed to a horizontal dial on the top plate.

Further, this design places the natural resting position of the index finger when it’s on the shutter release against the middle finger. In doing this, the grip provides the greatest range of motion to reach behind the shutter release towards other controls. Finally, it produces a grip with less bend in the wrist while holding the camera and still being able to access all the controls.

More importantly, this put the control dial in a place with a very low index of difficulty (Fitts’s law) making it very fast and easy to access while shooting.

Secondly, these advances in electronics allowed Canon’s designers to remove function specific dials from the user interface. This meant that main, and most easily accessible dial on the body, could be used to control whatever the most important function was for that mode. For example, in shutter priority AE, the dial would control the shutter speed; but in aperture priority AE, it would be able to control the aperture.

Further, Canon was able to concentrate the camera’s settings in a single location. Instead of having to look at various controls around the camera and lens, the single top LCD could tell you how the camera was configured (exposure mode, drive mode, metering mode, exposure compensation, shutter speed, aperture [in aperture priority AE, etc.]) all in in one place.

The designers of the T90 also recognized that due to the positioning of the hand on the grip, buttons could be located on the back of the camera accessible to the thumb. Though the function of these buttons would change with time, their positioning would remain unchanged.

Here too, the ability to access controls is dictate to some extent by the design of the grip controls. Canon’s grip angle allows the thumb to sit lower on the back of the camera, so it can cover more area, making more of the back of the camera more easily accessible.

Canon would exploit this in the 1998 released EOS-1 by adding a second dial (again, something that needs very small incremental rotary encoders to do due in a film camera) to the back of the camera on the film door. A design element that would become a standard feature of Canon’s UI.

Canon experimented with the details of their controls in many of their EOS film bodies. And things would of course evolve, but the overall pattern was set.

More AF: The EOS-1N

The next step in the evolution of Canon’s SLR interface would come in 1994 with the release of the EOS-1N. And again, technology would drive the changes.

With the release of the EOS-1N, Canon’s autofocus system was now sophisticated enough to support 5 AF points. This meant that there was now a newfound need to change which AF point is active. To accomplished this, Canon shuffled around functions on the camera again this time. In this instance, the rear top thumb buttons became AE-Lock and AF point selection, as we’re use to with modern Canon SLRs.

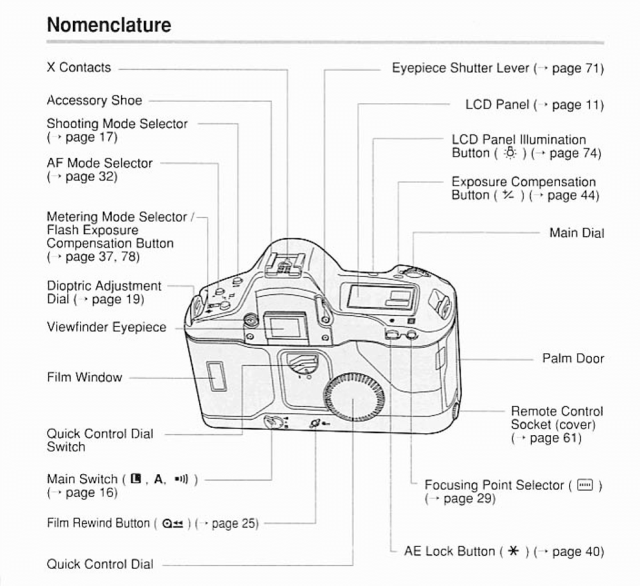

(Source: Canon EOS 1N manual pp, 10, downloaded from usa.canon.com)

This change, however, necessitated moving the existing exposure compensation button somewhere else, and this had to be somewhere easily accessible. For this, Canon chose to locate the exposure compensation button on the top plate, next to their existing LCD backlight button and just behind the main control dial.

Of course, a large part of why Canon was able to do this goes back to how Canon laid out front grip going back to the T90. While the buttons behind the command dial are more difficult to access compared to the command dial, the orientation of your hand and the range of motion of your index finger still makes them easily accessible.

Canon/Kodak DCS 1 and DCS 3

This brings this discussion to Canon’s first DSLRs. Well I say Canon’s, but in reality these were joint projects between Canon and Kodak. In this relationship, Kodak build the sensor module, and Canon provided a camera body to graft it on to.

As an aside, Kodak was working with Nikon at the same time, to build similar cameras around Nikon’s SLR line, and I’ll cover these when I get to Nikon’s UIs. Actually Nikon’s and Kodak’s involvement in digital SLRs predates Canon’s entrance into that area of the field by a few years.

Functionally, these cameras were a step backwards in terms of Canon’s SLR UI. However, this largely wasn’t Canon’s doing. The way these cameras worked was that a Kodak built sealed one piece sensor module was fitted to the back of a Canon EOS-1N body with the film door removed.

However, Kodak’s integration with Canon’s electronics was pretty compete. Though very early in the development of digital cameras, these cameras did support, for example, changing the ISO, and did so through the same button combination that a standard EOS-1N used. Moreover, the camera provided the back with information about shutter speed and aperture as well.

Suffice to say the technology clearly is still in its infancy. Worrying about the UI at this point, is probably not at the front of anybody’s minds.

That said, as far as UIs go, at this stage there wasn’t even an LCD display to review your images or even see what you were deleting. Which could be done in a last in first out fashion with the back’s delete button.

Canon EOS D2000 / Kodak DCS 520

In the 3 years from 1995 to 1998 to say that digital camera technology had advanced in leaps and bounds would be an understatement. The massive DCS series of cameras got a substantial overhaul in the size department, and a restoration of the missing parts of the UI.

While the Canon D2000/Kodak DCS 520 was still bigger than an EOS-1N, more similar in size to an EOS-1N with the added battery pack/vertical grip or a modern EOS-1D style camera, it was considerably smaller than it’s predecessors.

Finally in addition to restoring the missing parts of the EOS-1N interface, namely the rear quick command dial, the D2000 also introduced a LCD display to the back of the camera for reviewing images.

While my focus here is primary on the shooting side of camera interfaces, it’s probably worth taking a brief moment to talk about the review side too. In many ways, the need for and usability of a full color LCD screen to review images on was something that was clearly picked up on quickly by the manufacturers.

That said, when it comes to the physical interface for the review side of things, the design is somewhat more open in terms of efficiently placing controls on the camera. Generally speaking, most users holding the camera, as opposed to having the camera on a tripod, are going to hold the camera with their left hand around the left side of the body. The natural consequence of this is that placing the review, delete, etc. controls along the left side of the LCD places them in a good position to be pressed with the thumb.

In the case of the EOS D2000, this is what was done. To the left of the display, are buttons for record/tag, display/menu, and select.

In an interesting, almost regression, the D2000 doesn’t have a dedicated delete button. Instead the D2000 uses a rather complicated procedure involving:

- Pressing and holding the DISP/MENU and SELECT buttons at the same time, then

- Releasing the DISP/MENU button while continuing to hold the select button.

- Finally, using the quick control dial highlight either yes, no, or done on the the screen then releasing the select button.

As with many of the menu and secondary control solutions in early DSLRs the situation was complicated and confusing; far more so than it needed to be.

This concludes this section in my look at the evolution of DSLR UIs. While I’ve spent quite a lot of time talking about film and it’s influences on UI design, and really film SLR UIs in general, as I said at the start, DSLRs didn’t evolve in a vacuum. More importantly, at least in Canon’s case, their overall interface design reaches back far further than one might have thought. Moreover, I think if you’re going to talk about modern interfaces, it’s important to understand what they evolved from and out of.

In the next part, I’ll be covering what I call Canon’s early modern DSLRs. By this, I mean cameras that generally resemble what we use now, but aren’t quite there yet. To put at time frame on this, these would be cameras that Canon released in the early and mid 2000s. Like the 1980s where Canon was rapidly adapting to the electronics technology that was available, the early 2000s saw a similar rapid shift in designs around features and functionality as DSLRs changed the way photographers worked.

-

I know someone would probably quickly point out cameras like the Canon A-1 that had a ISO speed dial co-axial to the film rewind crank. In manual cameras, like these the ISO “dial” is a bias to the meter needle. You’ll also notice that this dial also functions as the exposure compensation dial. Since the actual sensitivity of the film is fixed by the film, as far as the meter is concerned the ASA and exposure compensation are the same things. Dialing in -1 stop of exposure compensation is the same as telling the camera that the film has an ASA 1 stop slower (e.g. ASA 800 + -1 EV exposure compensation is the same as ASA 400). ↩︎

-

While Canon claims they improved the sensor design, and perhaps they did, the system still used the same 9 selectable AF points with 6 non-selectable AF assist points that was in the original 5D released 5 years earlier. ↩︎

-

As an interesting aside, this change in Nikon’s UI came in the first new cameras to be released after the gaining a substantial number of professional Canon users. People who would would have already been exposed to easily accessible ISO buttons. While it’s pure speculation on my part, it may be possible that incoming high-profile Canon users were complaining about this to Nikon while the existing Nikon user base wasn’t. ↩︎

Comments

There are no comments on this article yet. Why don't you start the discussion?