Glacier Bay

Back in May I went on a cruise in Alaska. While this trip wasn’t purely for photography, I wasn’t about to leave my camera at home. This is the 6th installment of this series covering a number of photographic opportunities and how I felt they could be best exploited. The previous parts include shooting from a floatplane on Big Goat Lake in Misty Fjords National Monument, a glacier walkabout on Mendenhall Glacier, the photographic opportunities on Mount Roberts nature trails, riding and shooting from the White Pass and Yukon Route, and photographing the waterfalls along the Lynn Canal. This time I’m going to talk about Glacier Bay National Park.

There are places on this planet that one can visit and never be able to really express what it was like to be there. The Grand Canyon, for example, it doesn’t matter how big the picture is or how high of resolution, you can never quite convey the experience of actually being there. Glacier bay is one of these places, and unlike the Grand Canyon, Glacier Bay is far more ephemeral and fundamentally more endangered.

Glacier bay as a whole is a quite big, it’s 63 miles from the entrance to the bay from the Icy Straight, to the furthest end of the Tarr Inlet. There are currently 50 named glaciers in the bounds of the park, of which 7 are tidewater glaciers. All of this is to say that even if you’re traveling on your own small boat, there’s quite a lot of ground to cover and quite a lot of varied scenes to see and photograph. If you, like me, are on a cruise ship, you can expect to cover even less ground and spend even less time at any given location.

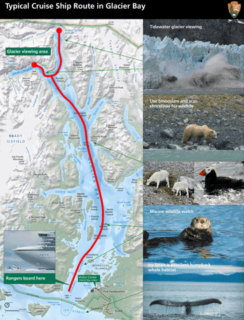

Depending on the cruise line and the ships schedule, and any other mitigating circumstances the exact experience in Glacier Bay will vary. Most ships cruise up the western side of the bay to the Johns Hopkins and Tarr Inlets.

In the worst case, like the Holland America cruise that charged up the bay ahead of our ship, is that the ship heads straight to the Tarr inlet and Margerie and Grand Pacific glaciers; does it’s rotation, and heads right back out of the park.

Most ships will probably sail up the Johns Hopkins inlet which means a close pass—actually two, one in each direction—of the Lampaugh glacier (tidewater) and a distant view (~6 miles) of the Johns Hopkins glacier.

In our case, this was the only trip our captain would be making to Glacier Bay in the season, and he wanted to get the most out of it. Instead of just running up the western side of the bay, our captain routed us up the eastern side of the bay. I don’t have the exact routing, but I’m pretty sure that we passed east of North and South Marble Islands, and made a close pass across the mouths of Queen and Rendu Inlets. This provided comparatively good views of Carroll and Rendu glaciers.

We circled Composite Island around the east and north sides, and headed for Johns Hopkins inlet. At the furthest point that cruise ships are allowed we did a full rotation and headed back out along the southern side of the inlet. This provided great opportunities to see Lampaugh Glacier up close, and the view down the Johns Hopkins inlet to the Johns Hopkins glacier (~6 miles away) provided a spectacular view.

From the Johns Hopkins inlet the ship then cruised up the Tarr inlet and did a double rotation for the Margerie glacier. From there it was a leisurely sail back to the Icy Straights along the western side of the bay.

All told, our ships sojourn through Glacier Bay, provided good to great viewing opportunities for 4 tidewater glaciers (Reid, Lampaugh, Johns Hopkins, and Margerie) and 3 large mountain glaciers (Carroll, Rendu, and Grand Pacific).

Now I have to reiterate, this was an exceptional sailing for a cruise ship. Our neighbors in the cabin above us said that in the 7 inside passage cruises they’ve been on, this was the best and most extensive tour of Glacier Bay they’ve had. This is to say, don’t plan on your cruise covering this kind of ground unless it’s a small boat experience focusing on photography or nature viewing.

With the lay of the land out of the way, I guess it is time to start talking about some of the specifics of photographing glacier bay.

As I alluded to in the introduction, one of the biggest challenges to capturing Glacier Bay, and really one of the problems I consistently had in Alaska as a whole, is dealing with the scale of the environment. Compounding matters, there’s generally so little air pollution that distances are deceptive and thus scale of many thing is also deceptive. Heck for that matter, when you’re 60 or 70 feet off the water, or more, on a cruise ship distance is also deceptive.

As an example, when I was processing my images I was utterly frustrated by the ridiculous blue haze that I was getting in all my images of Johns Hopkins glacier. It wasn’t until I got back home and started pulling the USGS topo maps and NOAA nautical charts for the area that I understood that we were 6 miles from the glacier and the bay was more than a mile across that it finely dawned on me that I was looking at atmospheric haze and reflected blue/uv light contamination from the snow.

I approached this problem in two ways. First, I took a page out of Art Wolfe’s playbook on how he deals with Glacier Bay. I made a lot of images that focused on the more abstract nature of glacial faces, or at least were more focused than normal landscapes.

This approach I think works well, given that it’s hard to really convey the scale of what you’re looking at. Most of the tidewater glaciers in glacier bay are 100–200 feet tall from the water line. However, unlike a building or other manmade structure, there is very little to give you a sense of scale. A floating iceberg in front of the glacier can be the size of a large car, and a cérac that calves off can look like a tiny bit of snow and ice falling and be tons of material.

The only way to really effectively put this all in to perspective is give some kind of comparative sense of scale. Only there’s precious little available for that. The two most obvious examples for this are boats—which is challenging as they don’t generally put themselves in a position to provide you scale—and birds. However, birds only really work if you can make a very big print where they’re readily visible and obvious.

The other thing to remember is that glaciers are extremely dynamic subjects. Their surfaces are almost constantly calving. There might be a great image of a cérac or crevasse one moment, only to have the cérac calve off.

The other approach I took in glacier bay was to shoot material for high resolution stitched panoramas. My thinking being that if I can print the image large enough, and at high enough resolution, people can really see and appreciate the scale of the area.

Fortunately, working from a cruise ship in glacier bay made panos easy to shoot. There’s essentially no foreground to content with, so parallax errors are virtually non existent. I only made sure that I shot enough overlap to insure that the resulting pictures would stitch properly. I even had some success with a couple of multi-row panos.

On top of the glaciers, there are also some limited opportunities for photographing wildlife. Humpback whales feed in the lower part of Glacier Bay, and it’s certainly possible to catch them breaching and tail slapping from a cruise ship. There are also potential opportunities for photographing mountain goats, sea lions, eagles, orca, and porpoises. Though if you’re shooting from a cruise ship, all of the smaller animals will be far more challenging due to the distances involved.

As far as gear goes, for Glacier Bay, I shot almost exclusively with my 100–400mm zoom, even the landscapes that accompany this article were shot with the 100–400 zoom and stitched.

Glacier Bay does pose some interesting challenges for photography, especially from a cruise ship. However, I think even with the limitations imposed by being on a cruise ship there is plenty of opportunities to make solid images.

Comments

There are no comments on this article yet. Why don't you start the discussion?